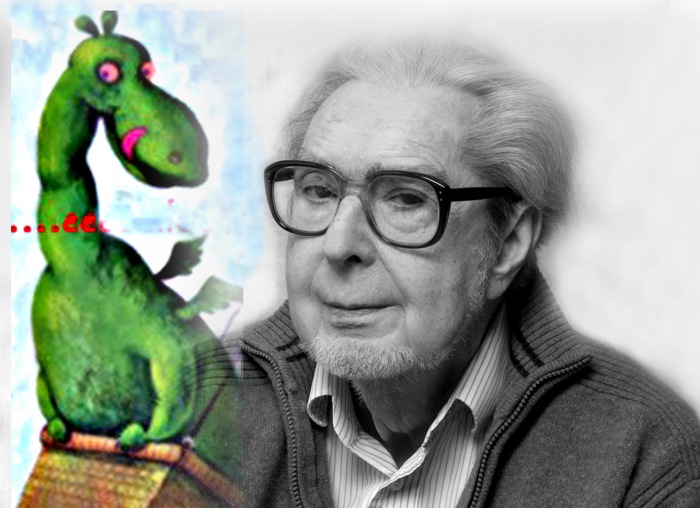

A Gentle Kind of Enlightener

Eulogy to Max Kruse, who not only gave Urmel to the world

max_kruse_urmel.jpg

Photo: Evelin Frerk

He descends from a famous family, his books were sold millions of times – and yet, Max Kruse remained modest all his life. Last Friday, Urmel inventor and gbs advisory board member Max Kruse died at the age of 93 in his hometown of Penzberg. Michael Schmidt-Salomon commemorates a good friend and foundation colleague.

Max was a man of quiet, gentle tones - as a writer and as a person. There was always a touch of melancholy when he spoke or wrote. He reminded me a little of the good-natured "Seele-Fant", who recited his sad ways in "Urmel aus dem Eis" ("Urmel from the Ice"): "Öch weuß nöß, was soll ös bödeutönön, dass öch so trauhaurög bön..." ("I don't know, what should it mean, that I am so sad?")

Unlike "Seele-Fant", Max's melancholy did not lead to lethargy. On the contrary: at the age of over 90, Max still displayed a creative power that I only found in exceptional cases in far younger authors. I remember asking him if he could give his Urmel to our project "Evokids - Evolution in Primary Schools" and if he might also be interested in writing an Urmel book on "Evolution". Max was on fire immediately. The legal questions were clarified in no time. And it only took him a few months to elaborate my brief sketch of a potential plot - Urmel involuntarily kidnaps Professor Tibatong's time machine and must survive numerous adventures in the evolutionary past - into a 165-page Urmel book.

During this time, the mails between us went back and forth wildly, as some tricky questions needed to be clarified regarding the book. For me it was an extraordinary pleasure to support Max in writing "Urmel Flies Through Time" - a childhood dream came true. I once loved the Max Kruse pieces of the Augsburger Puppenkiste very much, among others "Der Löwe ist los", "Gut gebrüllt, Löwe", "Don Blech", "Lord Schmetterhemd" and of course "Urmel aus dem Eis". Oh, how I laughed at the cheeky "Urmeli", who could not be educated at all by the domestic pig Wutz! Or at Ping and Wawa, who could argue so wonderfully about the "Mupfel"!

When I started working as a writer myself, Max Kruse was a legendary children's book author like Michael Ende or Astrid Lindgren. And so, when I received an email from a sender named "Max Kruse" in 2004, I didn't think, by any stretch of the imagination, that it might be "the" Max Kruse. Max, in all modesty, had asked, whether the Giordano Bruno Stiftung could also be supported by non-scientists - without mentioning himself at all. Coincidentally, my eyes wandered to the ending of his email address: "max-kruse-urmel.de". "This can't be happening!", I thought to myself. Carefully, I asked him - and indeed: none other than the father of the famous Urmel wanted to support the (at that time still largely unknown) Giordano Bruno Stiftung!

A Master of Connectivity

Of course we immediately agreed and appointed Max to our advisory board! Even the first mail Max wrote to us changed the foundation in a sustainable way. At his suggestion, we decided to establish the gbs circle of supporters and friends, and to open the advisory board of the foundation, which originally consisted only of scientists and philosophers, to artists. Both of these measures brought the foundation forward with giant leaps.

The fact that Max became our first artistic adviser and that we were able to meet in person for the first time a short time later was a great delight to me - not only because of the Urmel, but also because in the meantime I had read his four-volume cultural history of mankind "Im weiten Land der Zeit". This work, which was wonderfully presented by Hessischer Rundfunk with Peter Fricke as the main narrator, showed one of its great strengths as a non-fiction author: Max was a master of connectivity like few others were, an author who, where others can no longer see the wood for the trees, can easily identify the essential lines of development and make them comprehensible to the reader. His later books "Antworten aus der Zukunft", "Gott oder Nichtgott" and "Besen, Besen, seid's gewesen" - small masterpieces of enlightenment, which are unfortunately mostly overlooked in the shadow of the success of his children's books - also bear witness to this ability to thematically combine issues without unnecessarily straining his readers.

In the course of time

Those who want to understand who Max Kruse was and what made him so special should read his autobiography "Im Wandel der Zeit - Wie ich wurde, was ich bin". If it is at all possible to put the unchanging flow of time into words, Max has succeeded in this book. You not only see how little Maxl becomes big Max, but you also see your own life passing by in the mirror of this story. This is unusual for two reasons: first, because Max Kruse describes a completely different time (most of his readers probably did not consciously experience World War II), and second, because the family he comes from has little in common with the families of his readers: Both parents were not only unorthodox artistic freethinkers, but also real celebrities: His father, sculptor Max Kruse senior, one of the great visual artists of his time, was a member of the Secession and the Berlin Academy of Arts. He created stage sets for Max Reinhardt, portrayed Nietzsche, was in touch with Thomas Mann and Gerhard Hauptmann, and personally congratulated president Hindenburg on his 80th birthday. Mother Käthe, thirty years younger than his father, first manufactured the world-famous "Käthe Kruse dolls" for home use and later on a large scale, which revolutionised the toy industry.

As a child of such famous parents, Max Kruse junior did not know what to do with his life for a long time. He wanted to become a poet, but failed to live up to his own expectations. It was more of a coincidence, because mother Käthe Kruse needed a story for her dolls, that in 1948 he put "Der Löwe ist los!" to paper. The story was published as a children's book in 1952, but great success did not follow until 1964, when the Augsburger Puppenkiste made the book into a film - a stroke of luck for Max himself, who had previously earned his living as a copywriter, and of course for his many millions of readers, since without the Augsburger Puppenkiste probably neither the Urmel books nor the later enlightenment works "Im weiten Land der Zeit" or "Antworten aus der Zukunft" would have been written.

Death as redemption

I am convinced: Without Max Kruse's works, without his imagination, his empathy, his kindness, the world would be much poorer! It was an honour and a pleasure to know him amid my friends. Of course I am sad that he left, but it is a comfort to know that death was a redemption for Max. In recent months, he suffered increasingly from physical ailments. He hasn't been able to get out of bed in a while. Mentally active until the end, he had already inquired about the possibilities of euthanasia. For him (like most of us) it was a horror to be locked up in his own body with full consciousness, without reading, without writing, without being able to work. Fortunately, he was spared this fate. Max died last Friday as softly and quietly as he had lived: After a cerebral hemorrhage, he fell asleep and never woke up. Like this, and no other way, he would have wished for it.

Addendum

The farewell party for Max Kruse, at which Michael Schmidt-Salomon will be speaking among others, will take place on October 1 in Penzberg. Max Kruse's family kindly asked to refrain from donating flowers and instead make a donation to the account of the Giordano Bruno Stiftung (code: Max Kruse). Further information about the farewell party can be found here.